CNN

—

When people ask me how good of a player Willie Mays was, I give them a perhaps odd answer.

The San Francisco Giants basically gave Mays to the New York Mets for practically nothing in 1972, and a well past his prime 41-year-old Mays was the best overall hitter – as measured by his ability to get on base and hit for power – on that solid Mets squad.

Of course, the more normal way to know how good Mays was is that he remains, statistically, the best player who played his entire career in the last century and is in the Hall of Fame.

But if you truly want to know how great Mays was? You had to watch him play.

I couldn’t help thinking of my Father when I learned of Mays’ passing last night on “The Source.” I mentioned him almost immediately. You see, my Father watched Mays play when he came up as a rookie for the New York Giants in 1951. He considered Mays the best player he ever saw from the moment he laid eyes on him in that inaugural year.

Harry Enten reacts to death of Willie Mays

Mays supercharged that ‘51 Giants squad and helped them overcome a 13.5-game deficit in mid-August to win the NL pennant over their crosstown rivals, the Brooklyn Dodgers, thanks to the Shot Heard ‘Round the World. It remains, in my opinion, the greatest comeback in baseball history. Mays won Rookie of the Year that season.

It was three years later, however, when Mays became a baseball legend. After serving in the military for over a season, the man nicknamed the “Say Hey Kid” – who had a great song written about him playing on that name – dominated the National League.

He led the league in batting average, slugging percentage (a measure of power), triples (one of the ultimate measures of speed and power) and on-base plus slugging (OBPS), which combines all of it into one metric.

And yet, I don’t think most remember Mays’ 1954 MVP season for his offensive exploits; people like my Father remember him for a play he made during Game 1 of the 1954 World Series.

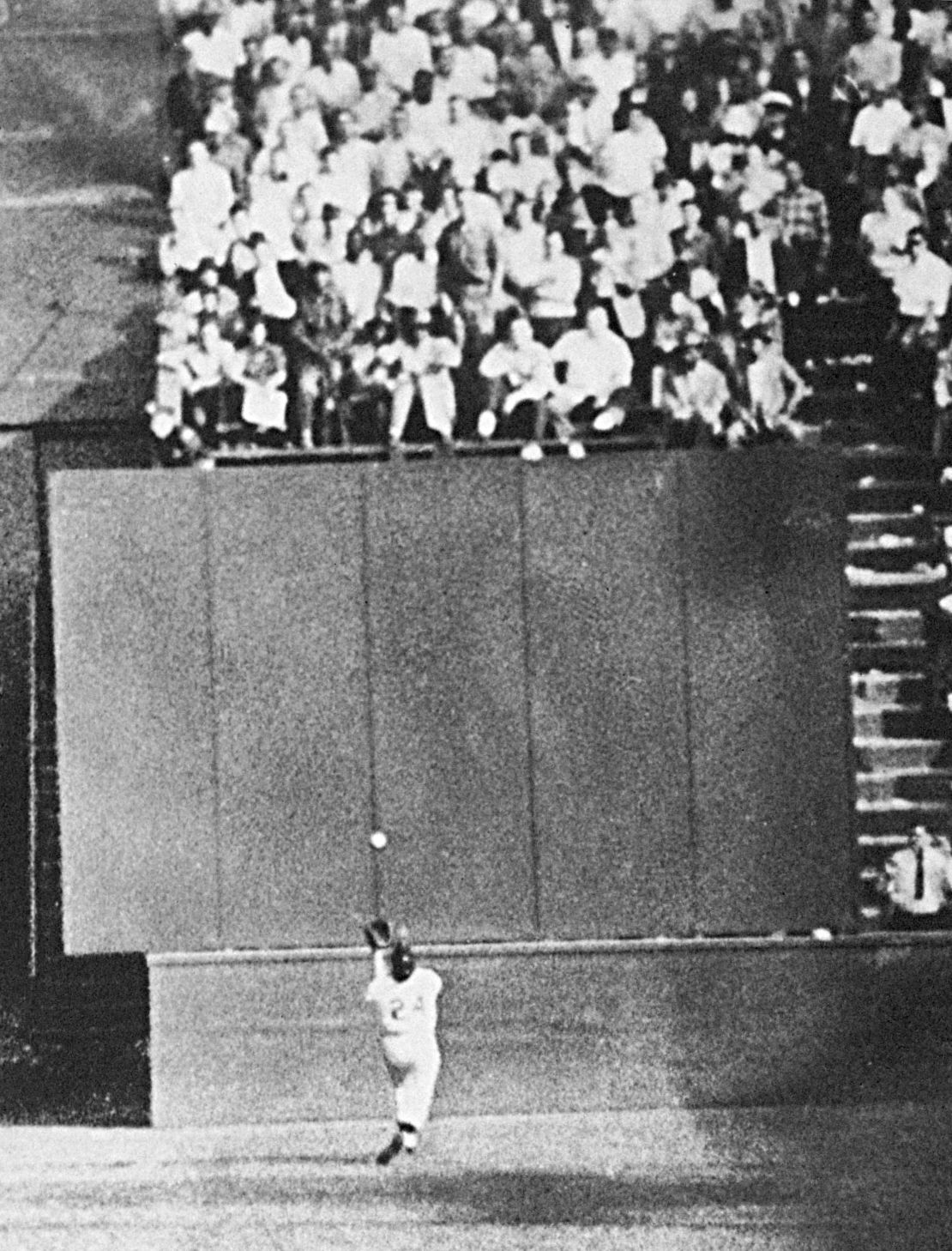

Let me set the scene: the game is tied 2-2 in the eighth inning. The Cleveland Indians have runners on first and second with no one out. Cleveland power hitter Vic Wertz is at the plate, and he hits a long fly ball into the truly cavernous center field at the Polo Grounds in New York.

Mays, who roamed center field for over 20 seasons, went back more than 400 feet and made a difficult, over-the-shoulder catch seem easy. He then fired the ball back into the infield to ensure that no runs would score.

The Giants would go on to win the game and sweep the series in four games. It was their swan song in New York, as they moved to the West Coast after the 1957 season.

Mays never understood why people thought that catch was amazing. For him, it was relatively routine.

What was unique about this catch, beyond being in the World Series, was that video cameras captured it in an era from which we don’t have many recordings.

That short splice of film is our version of getting to see Mays play. It’s our rare glimpse into a man whose defensive prowess was far more than that one catch.

Mays was the best defensive player at any position that entire season in the National League, according to advanced statistics.

He is, by those same metrics, a top-five defensive outfielder of all time, and those statistics – given we don’t have a lot of video from the era – don’t even really take into account his obviously great arm.

The fact that I’m talking about the defense of a man who for a long period of time was third all-time in home runs – and remains sixth – tells you everything you need to know.

Mays wasn’t just defense, though he excelled at that.

He wasn’t just about hitting for power, though he excelled at that.

He wasn’t just hitting for average, though he excelled at that.

He wasn’t just about speed, even though he excelled at that and led the league in stolen bases four times.

Mays was everything – and he was so for over 20 years. Mays was, as my friend and esteemed sports columnist Neil Paine calculated, the most complete ballplayer in history.

Baseball fans talk about finding five-tool players – those who hit for power and average, have speed and defensive abilities in terms of range and arm – like a miner trying to find gold. Well, we found our gold in Mays.

But again, Mays is more than just numbers. He was one of our last links to multiple eras of baseball history.

Mays oversaw the expansion of baseball to the West Coast in 1958, when it had previously been played on the Major League level only east of the Mississippi River. He was the first superstar on the West Coast.

Mays was also the last superstar with us who made his name playing in New York during the 1950s. It was baseball’s golden era; a time when America came out of World War II with a booming economy and during which baseball continued to outrank football as America’s favorite sport and pastime.

And if Mays wasn’t good enough, he actually added a few hits to his storied, record-book career a few weeks ago when Negro League statistics were integrated into the MLB record books. Mays was one of the last living stars who started his career in the Negro Leagues in 1948 for Birmingham Black Barons.

I like to joke that Mays was so great that he was still compiling hits at the age of 93.

Indeed, he remained a hit with anyone who saw him play. Long after his career was over, Mays – when he would come back to New York – lived down the street from us in the Bronx. My Father would see him on walks and knew he had to get his autograph.

Mays gave my Dad that autograph, and he kept it in his office until he passed. Mays is a big reason why my Father was one of the few people who wore a New York Giants baseball cap throughout his later years. I bought at least three of them for my Dad because he had one on his head all the time and literally wore them out.

It’s a connection I try to carry on to this day whether it’s by wearing a New York Giants baseball hat on television or by answering “the New York Giants” when asked what baseball team I root for.

Now, excuse me as I go try and find that Mays autograph to honor the greatest player anyone I know saw play.