Bussiness

Pearl Street, Niagara Falls and the war of the currents: The eccentric beginnings of New York’s bright lights

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen electricity was first rolled out in New York in the late 19th Century, sparks flew between competitors. Today, the city is attempting to complete its electric evolution.

On 7 June 1882, the lights were switched on in a lush Madison Avenue brownstone mansion, making it the first private residence in New York to be illuminated only by electricity.

Inventor and electricity pioneer Thomas Edison and his colleagues had installed wiring throughout the walls of the house, which belonged to financier and investment banker J P Morgan. Incandescent lightbulbs had been added to every room – 385 in total.

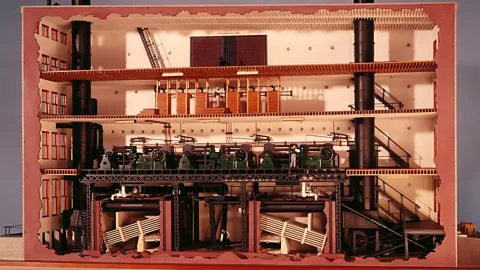

In the cellar beneath a nearby stable, a steam engine, boiler and electrical generators clanked and roared away, writes historian Jill Jones in her 2004 book Empires of Light. Connected to the house via underground cables, these were manned by an expert engineer, who started duty at 3pm and finished at 11pm. Sometimes, when the family forgot to watch the clock, they would be suddenly plunged into darkness at this point, Herbert Satterlee, Morgan’s son-in-law, later wrote.

The Morgan’s neighbour, Mrs James Brown complained the machines made her whole house vibrate. Morgan, though, was reportedly pleased.

But this milestone was just a test run for Edison. “Edison didn’t want to build small, separate generators in millionaires’ basements; he wanted infrastructure to feed the whole city,” writes historian Alice Bell in her 2021 book Our Biggest Experiment: A History of the Climate Crisis. “Indeed, the beauty of electricity was that you could distance yourself from the dirt of the generation of power.”

Getty Images

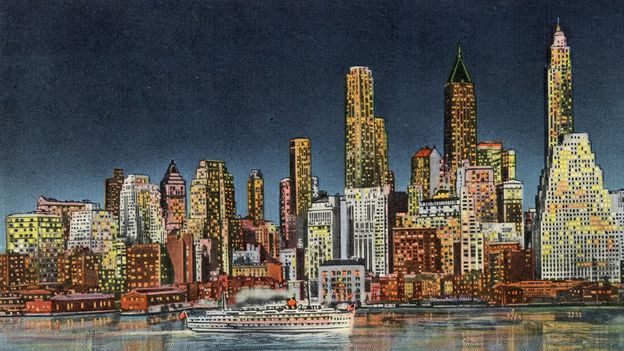

Getty ImagesIn the late 19th Century, New York State and in particular New York City became a global epicentre of emerging ideas on how electricity could be used in everyday life, and the experiments to roll out the first electricity systems to the public.

As the scene of some of the world’s first power plants, street lighting and power networks, as well as an infamous “war of the currents“, New York played a pivotal role in the rollout of what electrical systems look like today.

“New York City was the first place where commercial electricity was built and sold at scale in the US,” says Robert Lifset, associate professor of history at the University of Oklahoma who specialises in the energy history of the US – although there were “quite a few” controversies that took time to be resolved, he adds.

At the time of these early experiments, electricity remained a strange, relatively new curiosity to most people. The thought of using electricity to power our entire lives was still a distant, rather odd idea. Today, it has become one of the most important ways we know of to avoid more carbon emissions.

But to understand New York’s long and bumpy road to electrification, you need to know how it all began.

Early power

By 1880, while some homes were lit by electricity, they were rare and, like J P Morgan’s, required individual generators. In fact, gas was more commonly used for lighting in New York. “Manufactured gas – essentially the gas produced by heating coal – was being piped to the wealthier parts of the city, lit and used for illumination,” says Lifset.

But the city was already eager for a better alternative to gas, says Harold Wallace, curator of the electricity collections at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington DC. “Politicians are complaining about companies that aren’t maintaining their systems well, users are complaining about odours and impure gases that are being used, and there’s a lot of calls for something to replace, or at least provide competition for, the gas systems,” he says.

An enthusiastic group of engineers and inventors centred in New York were eyeing this opportunity. The sheer size and density of New York, already a very populous city, provided an incredibly handy backdrop for field tests on electricity networks. “Being able to test at scale in New York City was really advantageous,” says Wallace. “[Edison and his team] figure if they can make the system work in New York, then they should be able to scale it down, basically, and make it work in other markets.”

Another reason New York City was such an important early hub for the development of electric power systems was its stature as a finance centre, adds Wallace. “[It was] a locus for investors and what we today would call venture capital.”

Alamy

AlamyBut the dazzling arc light was too bright for use in homes, and for some, too bright to use anywhere. New York’s real field test was still to come.

A softer light

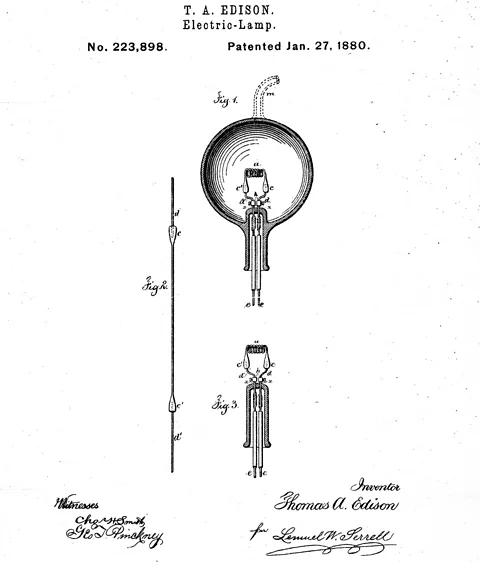

The inventor Thomas Edison had gained widespread fame with his inventions of an improved telegraph and telephone, as well as the phonograph, the first device to play back recorded sound. In 1878, he saw arc lights for the first time and quickly became obsessed with the potential for rolling out electric lighting more widely, writes Bell.

In 1879, he announced that he had invented the first practical incandescent lightbulb – which avoided the intense brightness of arc lights – at his research laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey.

Dynamos, or self-excited generators, invented around 1870, now existed which could put out a “tremendous amount of electric power”, sufficient to power arc lights and other high-power electrical systems, says Wallace. The components of domestic lighting were ready for use.

It featured six coal-powered generators using several miles of cables laid under the street. These under-street cables gave an advantage over the hated muddle of overhead wires starting to criss-cross New York, although installing them did require the temporary inconvenience of closing off streets.

The station provided electricity to homes at a price comparable to gas, and by 1883 had over 500 customers. “Customers around Pearl Street were given the special introductory offer of a box of lightbulbs for free, and block by block, the lightly twinkling electric-lit cityscape we are now so familiar with emerged from the shadows,” writes Bell.

Edison was adamant that he was creating a lighting system, not a general overall electrical system, which evolved later, says Wallace. But he did want to make sure it was competitive with gas, he adds, coming up with a figure of a 16-candlepower output, so as to top the 15-candlepower he had surveyed as the average light produced by a gas jet in New York City.

Current wars

Edison had plans to expand his system throughout Manhattan and New York City, says Wallace. As the Pearl Street station used purely direct current (DC), though, it could only power homes within around a quarter mile radius, he says. This is because the voltage of DC could not be easily converted at the time, making it hard to transmit DC at high voltages, thus meaning DC electricity would see large losses over long distances.

A larger DC network would therefore require many small stations. “Edison was going to put a series of these stations throughout Manhattan,” says Wallace.

Alamy

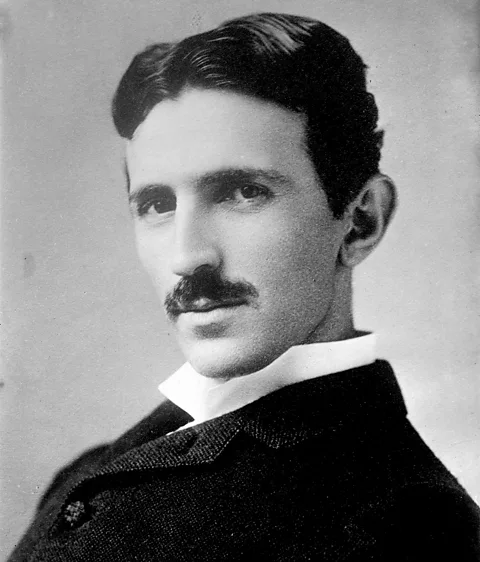

AlamyWhile working for Edison, the charismatic Serbian-American scientist Nikola Tesla had proposed using a different electricity system based on alternating current (AC). “With alternating current, you can transmit the power over much further distances,” says Wallace. “You can have a few much larger power stations.” AC could be more easily converted between high and low voltages using transformers, which only work on AC electricity.

But Edison dismissed the proposal, arguing his more established DC was safer than the experimental AC which had “no future to it”. Tesla soon quit and teamed up with railway entrepreneur George Westinghouse, who was also interested in the ability of AC generators to transport electricity over long distances.

This was to be the world’s first large-scale hydroelectric power plant. “The two Niagara stations would generate a mind-boggling 100,000 horsepower, equal to all the central stations then operating in America,” writes Jones. “Never had electricity been generated on such a scale.”

The war of the currents was hugely important in determining the future of electrical systems, according to Lifset. “The switch to AC power allowed for the use of larger power plants located further away from their customers,” he says. “This served as the foundation for the industry’s emerging business model. It’s what allowed electricity to become cheap and was a significant factor in the spread of electrification.”

Over the following decades, electrification swept through New York. Early adopters included commercial businesses looking to attract customers, the wealthy and the city itself, says Lifset. “Industry was not far behind. It took longer for middle and working-class people to get access.” By 1899, though, anyone in Manhattan could connect to electricity.

Alamy

AlamyElectricity also spread out further afield, although not to everyone. “Most urban landscapes in the US were electrified by the 1910s,” says Lifset. “[But] it took considerably longer for this process to play out in rural America.”

Back to DC

The insatiable rise of these technologies mean we are actually using growing proportion of DC in electricity consumption, while some of world’s longest transmission lines now use high-voltage DC electricity. Some researchers argue that this increases the case for direct DC power to end users over a century after AC won out.

Edison, Westinghouse and Tesla had proven that electricity was a game changer for lighting. But it wasn’t the end for gas. “The gas industry went back, they upgraded their systems, they came up with new refinements so they could put out cleaner gas that didn’t have the smell or create quite as much soot,” says Wallace. “They also came up with new applications.” The industry began promoting gas for cooking, heating and even refrigerators.

Electricity also soon expanded to more than lighting. “Very quickly within the 1880s other applications occur,” says Wallace, including electric fans and irons as well as larger items like refrigerators and stoves. “[Electric refrigerators and stoves] take quite a bit more of an investment, so most people couldn’t afford them early on, but they could afford an electric fan, or especially an electric iron was marketed very heavily early on.”

Since most tenements or apartment homes had only a single light bulb socket hanging in the middle of the room, these early irons and fans would have light bulb bases that could be attached to an adapter and plugged into this socket, says Wallace. “It was not until the late 1890s, into the early 1900s, when what they called convenience outlets, [what] we think of as wall sockets today, first really started coming on the market.”

A new transition

Electricity has long reached dominance in the industrial world for lighting and most appliances. But when it comes to heating and transport, fossil fuels remain the principal player.

What’s more, while some electricity comes from renewables like hydropower, as it did in Buffalo in the late 19th Century, most comes from coal and gas generating stations. Even today, fossil fuels account for the majority of electricity generation in New York State, in the US and around the world.

So in the current era of climate crisis, New York, like the rest of the world, is facing another energy transition: the move from fossil fuel to renewable energy. A huge piece of the puzzle in how to do this is further electrification of our energy use – in particular, heat and transport.

“New York state has been an energy pioneer for 150 years…electricity was made here,” she said. “[Today], we are called to invest in an emissions-free energy economy… Let’s engage, let’s strategise and solve these [emissions] problems with the same can-do spirit.”

*Jocelyn Timperley is a senior journalist for BBC Future. Find her on Twitter @jloistf